Anatomy Of A Pit Stop

How Seconds Standing Still Can Win A 150mph Race

There are only three situations when TV directors will never cut to adverts during a Formula 1 race: just before the start, as the leader approaches his final lap; and during a pit stop window.

That’s how important pit stops have become. Since mid-race refuelling was introduced to Formula 1 (as recently as 1994) – and with overtaking moves rarer than ever, pit stops have become the prime opportunities for gaining places. And the most vulnerable time in terms of losing them.

Most people who watch F1 regularly know that a good (and flexible) race strategy can allow a driver frustratingly caught behind a rival to put in some fast laps while in the clear and then get out ahead after refuelling and a tyre change.

A pit stop is never as easy as it looks. For seven to eight seconds (if all goes well), the drivers’ chances in the race are in the hands of his pit crew. All the racer can do is sit and wait.

According to Gerard Le Coq, Toyota’s “lollipop man” (who holds the sign that tells the driver when to stop and when to shoot off again), “It is hard to say if I can help the driver win. I think it is more a case of helping him not to lose.”

Toyota is a team that knows all too well the difference a mistake in the pits can make. In 2002 they were set to be in the points in only their second race when Alan McNish came into the pits to find only three new tyres waiting for him. Since then, they’ve worked to become one of the fastest teams on the grid, regularly producing some of the top five quickest turnarounds at Grands Prix in 2004.

Being part of the pit crew is one of the most exciting parts of a race team. It is also potentially one of the most hazardous. The mechanics get no danger money and it’s almost impossible for them to find life insurance. Yet few would swap their job in the pit lane for anything else.

We talked to some of the key players in the Toyota pit stop crew about their duties, the dangers – and what can go wrong…

The driver – Olivier Panis

“I need to arrive as quickly as possible but as precisely as possible. If I stop a little too far forward or back of the spot, the guy on the fuel hose has a hard job moving to me, because it is so heavy, and you can easily lose two or three seconds. The worst thing that can happen is stalling the engine.”

Lollipop Man – Gerard Le Coq

His first job is to guide the incoming car to the exact stopping point by lowering the ‘lollipop’ to a stop position right in front of the driver’s helmet. “I have to hold it exactly still – any movement and he will think it’s time to blast off. When the rear wheels are on, I can turn the lollipop from “Brake On” to “Brake On & In Gear”. The second I see the fuel nozzle off I release the driver. I’ve never been run over, but if things go wrong, I could be.”

Front Jack – Thomas Mattes

The front jack operator raises the car as soon as he’s sure the car is in the right position to allow the fuel nozzle in. If there has been an accident and the nose section needs changing, it is his job to remove the broken one. Mattes is in one of the most dangerous positions – even with a rev limiter on, the Toyota is still doing 50mph, and the sharp end of an F1 car is not something you want to introduce your shins to. “The worst moment is if the car has a clutch problem. Then you don’t know if it’ll stop on the spot – and if it stops a metre too late, I’m in real trouble.”

Wheelnut Man – Jens Luy

One of a three-man team on each wheel – the other two take off and put on the wheels – it’s a stressful job because it’s easy to destroy the wheelnut thread and get it stuck. On a certain team, these men remain anonymous to protect their families from vengeful fans who blame them for a loss. “We do train to do it as quick as possible, but usually in the race you have more time because fuel is still going in. The most important thing is to do it safely.”

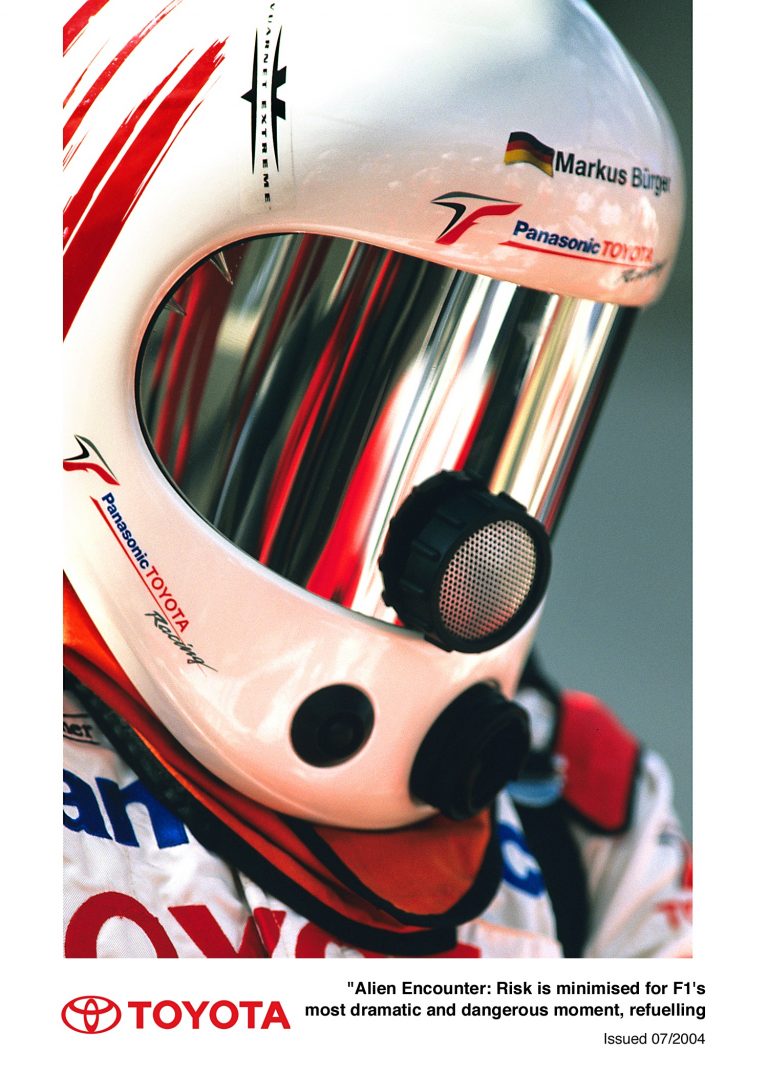

Refueller – Markus Berger

Berger, supported by two helpers, has to lift a heavy nozzle over his shoulder and get it into the tank the moment the car arrives. At high pressure, it delivers 12 litres of high-octane fuel a second. “There is a light on the machine which tells me when to release the pump. At that moment I have to get the nozzle out quick. It’s scary if the car is released when you’re not done – it happened to one team recently, sent the guy flying – and it has happened to me but the car only moved a little.”

Slow Motion Replay: A pit stop timetable – second by second

- 0 secs: Le Coq lowers the lollipop; Panis stops; Berger shoves the hose in, as a colleague holds up a fireproof board to stop any spilt fuel hitting the hot exhausts.

- 1 sec: Luy and the back jack man lift the car, while Luy and three others remove the single nut holding each wheel on.

- 2 secs: At each corner, one man removes the old tyre; another readies the new one. Someone else wipes Panis’ visor.

- 3 secs: New tyres are fitted. If adjustments to the wing angles are required, they’re done now. The cleaner checks the air intakes for blockages.

- 4 secs: Luy replaces his wheelnut then holds the air gun above his head.

- 5 secs: With all four air guns up, the jacks are lowered and Le Coq flips the lollipop to the equivalent of a red and amber light. Panis shifts into first gear.

- 6-12 secs: (depending on how much fuel is needed): When the right amount of fuel is in, Berger pulls the hose out; Le Coq glances at the pit lane to see that it’s safe to pull out and lifts his lollipop. Panis accelerates away.

ENDS